Saving fifteen hundred people. A first responder about the evacuation from Mariupol and other cities

"War has changed something in us. Perhaps not the work itself, but the people. It has changed the way people approach the work they do. They’ve become a bit more responsible, more humane," says Valentyn Stetsenko, deputy chief of the 8th unit of the State Emergency Service of Ukraine in Zaporizhzhia. For over 15 years, he has been involved in mitigating the consequences of various emergencies, such as industrial accidents, car crashes, and both man-made and natural disasters. Although many of them involved lifesaving operations, none of them made him confront such large-scale devastation and omnipresent human suffering as the evacuation of people from Mariupol and other Russia-occupied territories in the Ukrainian South.

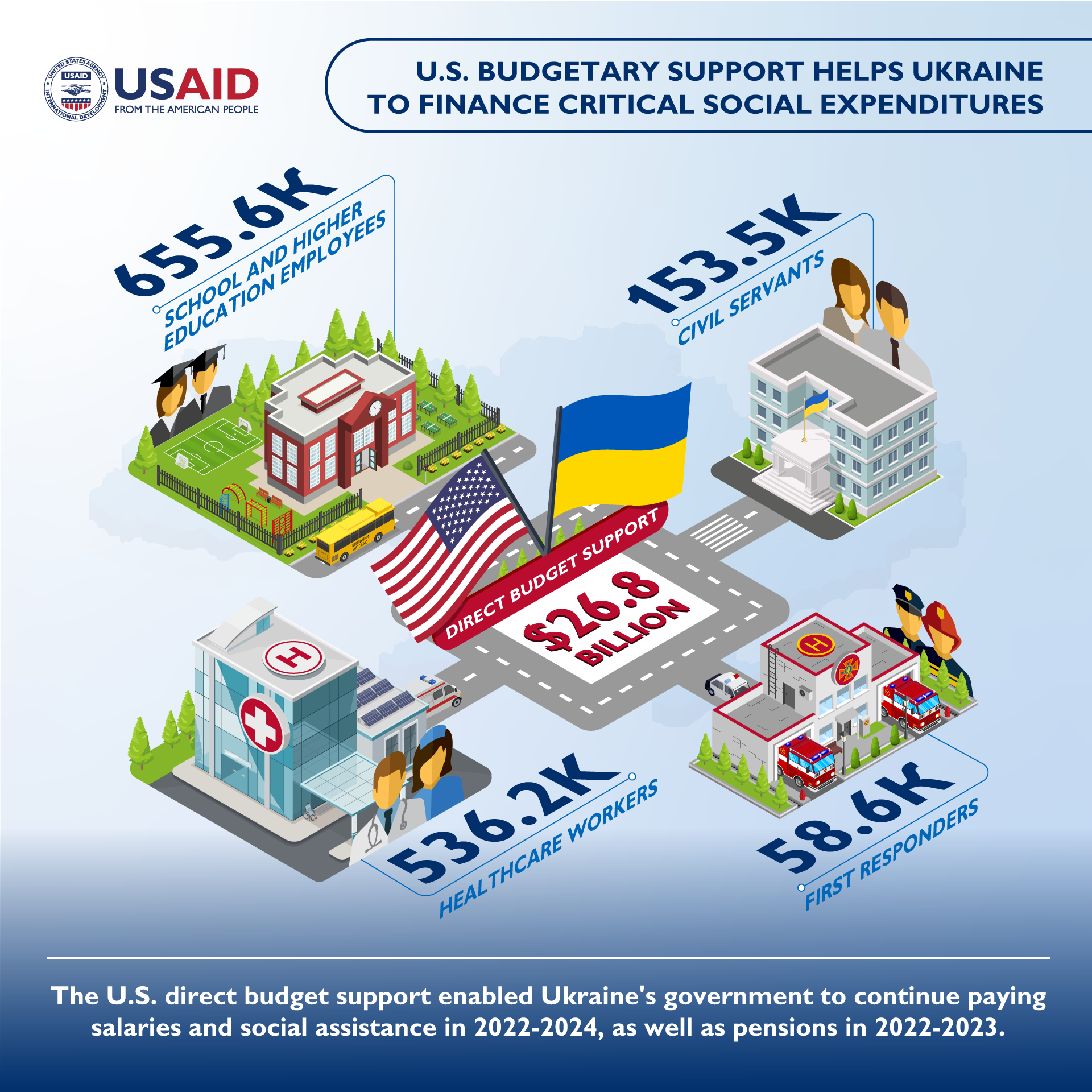

Valentyn is one of the 58,500 SESU workers who have been able to carry on their crucial wartime efforts thanks to the support of the American people. Since spring 2022, the United States, through the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), has provided the Ukrainian government with $26.8 billion in direct budget support. These funds, which go directly to the Ukrainian state budget, are used to reimburse critical social expenditures, including the salaries of first responders from the State Emergency Service.

During this time, the United States became the largest individual country donor of economic assistance to Ukraine, having already provided $26.8 billion in direct budget support.

Disbursed through the World Bank's mechanisms, American funds are directed into the Ukrainian state budget, reimbursing the government's expenditures on salaries for over 1.4 million workers whose uninterrupted work is most crucial for today's survival of Ukrainians and the future recovery of the country — first responders, healthcare workers, educators, and civil servants.

Thanks to US budgetary funding, the Ukrainian government also continues to support the most vulnerable members of the population by providing social assistance to internally displaced persons, low-income families, and others.

Fire and rescue operations specialist Valentyn was not obliged to participate in evacuations but joined voluntarily. It was the second month of Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine and the second month of fighting in Mariupol. Soon, the city was completely cut off from the rest of Ukraine by Russia’s occupation forces, leaving thousands of soldiers and civilians trapped inside without food supplies, access to water, electricity, gas, phone, and internet connection —and under constant fire. As people were leaving their hideouts in the basements under the shellfire to scout for food and melt snow to get drinking and cooking water, death became a frequent occurrence. The most secure remaining place was the Azovstal steel plant, with deep and heavily protected basements. Eventually, it became the last refuge for many civilians and defenders of Mariupol after the rest of the city had fallen to Russia’s occupation forces.

By the end of April 2022, an agreement was reached to evacuate civilians sheltering in Azovstal to territories controlled by Ukraine. The evacuation lasted until May 7th. "I was offered to go to Mariupol, accompany the convoy: provide everything necessary during the trip and return to Zaporizhzhia. I was warned that the situation in Mariupol was very difficult; there was still fighting," Valentyn recalls. The warnings did not stop him because he knew the people needed help to get out.

City of empty eyes

Valentyn entered Mariupol together with a group of State Emergency Service first responders, who accompanied an evacuation column of 15-20 city buses, a Red Cross car, and a UN car. The buses were supposed to transport civilians from Mariupol to Zaporizhzhia.

The rescuers' first impressions of the city upon entering were depressing.

"The city was destroyed, burning, smoldering. And people were walking around ’empty,' looking at us with pleading eyes," Valentyn recalls.

Later, the mayor of Mariupol, Vadym Boychenko, reported that as a result of the fighting, the city's infrastructure was 90% damaged.

"I remember a huge stench in the city. You see, it was already warm... And these spontaneous graves in green zones, parks, with crosses made of sticks and wire," Valentyn recalls what he saw. According to official Ukrainian estimates, at least 20,000 civilians died in Mariupol.

When the evacuation convoy reached Azovstal, Valentyn expected that people would try to leave the city as soon as possible, but at first, the civilians refused to leave. There was a reason for the local’s distrust: previously, Russia’s occupation forces had already tried to lure them out with promises of evacuation to Ukraine, only to later take people away to other occupied territories or Russia proper. Eventually, the convoy members managed to convince them.

However, not everyone was able to leave the territory occupied by Russia’s army. "On the way back, we had to go through the filtration camp first. Some women were taken away and did not go with us any further. All those who were released continued to travel with us to Zaporizhzhia," explains Stetsenko.

In total, Valentyn's group managed to rescue more than 150 women and children from the steel plant. They rode in silence as people were leaving their destroyed home city. But when the convoy reached Ukrainian territory, many people started to cry. "I think they were tears of joy because people did not believe we would make it to Ukraine’s free territory," the firefighter adds.

Saving people from shelling

The trip lasted for five days and was one of five evacuation convoys Valentyn participated in during the war. In addition to Mariupol, he accompanied convoys from Orichiv, Gulyaipole, Tokmak, and Berdyansk, and in total, helped to save 1,512 people and 12 busloads of people from the occupation (in different trips, the approach to counting people was different — Ed.). Each trip had its difficulties.

Sometimes, Russia’s soldiers held buses full of evacuee women and young children at roadblocks for several days without reason, especially during the summer heat when food and water ran out quickly.

Russia’s military did not shy away from looting either. "There were also checkpoints where they took grain, water, shampoo — whatever we brought for the people. They took it for themselves," says Valentyn.

One of the challenges for Valentyn was an incident on the so-called "road of life" — a stretch of road near the village of Kamyanske, where one has to navigate through rough terrain to reach the regional center. After the rain, the road was a muddy mess, and buses with people couldn’t get through. First responders of the State Emergency Service had to escort people on foot and pull buses from the mud with tractors. "There were children and women there. We had to make them stay in one place because everything around us was mined," Stetsenko recalls. Fortunately, there were no casualties.

Now that the mass evacuations are in the past, Valentyn is back to his "usual" wartime responsibilities: saving people in the aftermath of the shelling. Every time a rocket hits a building and causes massive destruction in Zaporizhzhia, Valentyn, and his team clear the debris and save people trapped under it. At the beginning of the full-scale invasion, the first responders switched to a tighter schedule — one day on, one day off. However, after some airstrikes, they had to work at the debris sites for up to two consecutive days. "It's not like in movies or on TV. There's a lot of dust, construction debris, broken furniture. You can be on the brink of exhaustion, but when you realize there’s someone here you can save, someone who needs your help, and their life depends on it, somehow you find the strength. It's like a second or third wind," he says.

Zaporizhzhia is very close to the front line, so shelling of the city or suburbs is an everyday occurrence. Often, firefighting and rescue teams, like Valentyn's, are assisted by locals who also start clearing the debris or bring coffee, tea, and sandwiches. According to the rescuer, in such cases, the main task for professional rescuers is to organize people properly, not only to speed up the debris clearance but also to protect them from additional dangers. For example, Russia’s forces repeatedly shelled impact sites in Zaporizhzhia when rescuers arrived to eliminate the aftermath. In one such incident in the spring of 2023, Valentyn’s colleague died.

Despite all the challenges and difficulties, Valentyn emphasizes that he is ready to continue working and help Zaporizhzhia overcome the consequences of the war: "I don't know where the strength and inspiration comes from — maybe it's the thirst for victory, maybe I want all our people to return home. But I can and will do this job."

All photos provided by the SESU.

Comments (0)