Demining cradles and dead bodies. Deminer Roman Shutylo on the work of SESU pyrotechnicians

Together with his crew, Roman Shutylo, the head of the pyrotechnics division of the special emergency rescue squad at the State Emergency Service of Ukraine (SESU), starts work at 7:30 a.m. He puts on 12 kg (26.4 lb) of equipment, including bulletproof vests, helmets, knee pads, first-aid kits, and other gear to make his job slightly safer. He receives plans for the day and undertakes one of the critical tasks to ensure the safety of Ukrainian citizens — they find and destroy mines and unexploded ordnance. According to SESU, since the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion, they have found and destroyed more than 500,000 explosive devices. And yet, this work is far from over. This is a large-scale challenge as 30% of Ukraine's territory, or around 174,000 square kilometers, is polluted by mines today.

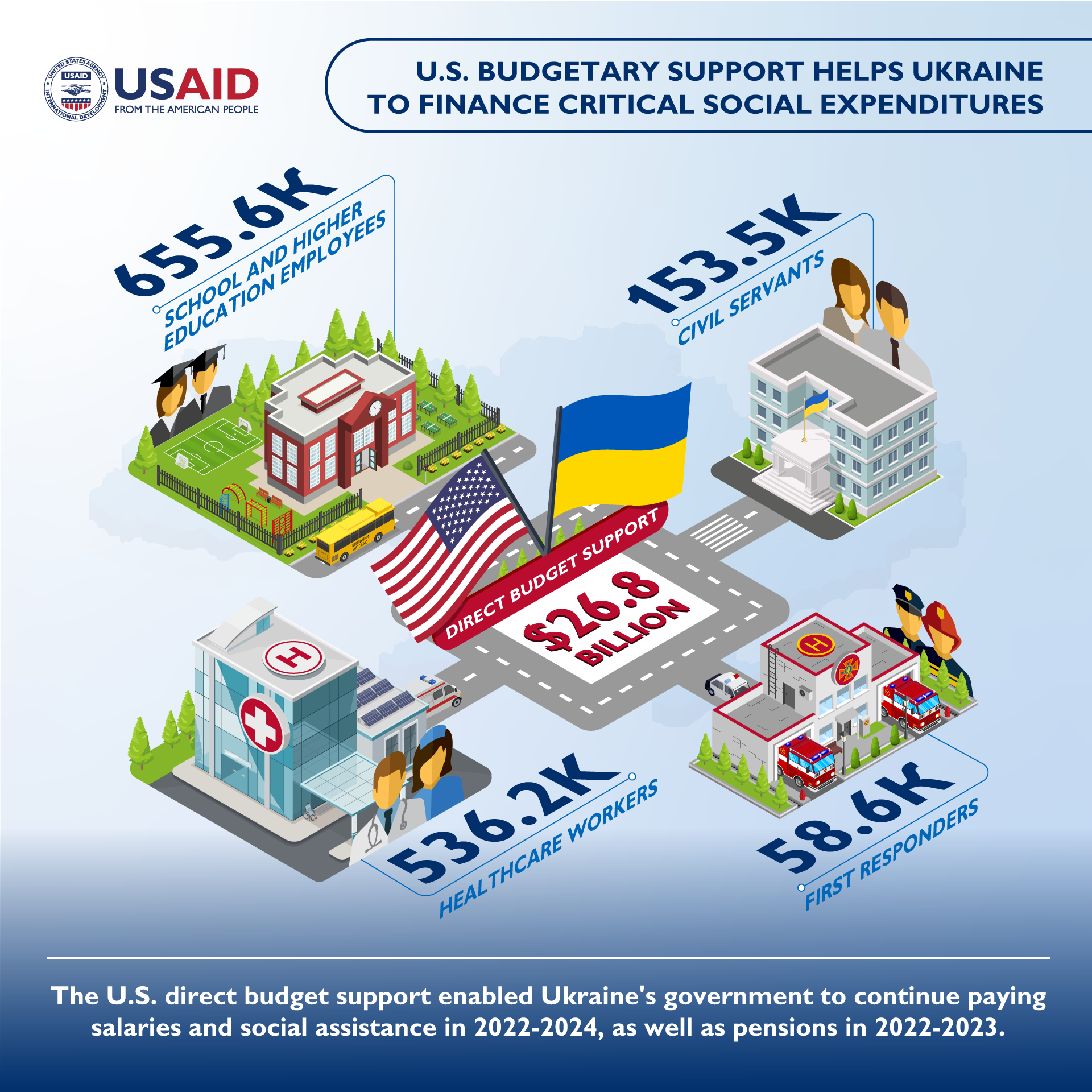

To support the work of specialists like Roman, the U.S., through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), has provided the government of Ukraine with $26.8 billion in direct budget support since the spring of 2022. These funds help to offset critical social expenditures, including salaries for more than 58,500 employees of SESU.

Disbursed through the World Bank's mechanisms, American funds are directed into the Ukrainian state budget, reimbursing the government's expenditures on salaries for over 1.4 million workers whose uninterrupted work is most crucial for today's survival of Ukrainians and the future recovery of the country—first responders, healthcare workers, educators, and civil servants.

Thanks to US budgetary funding, the Ukrainian government also continues to support the most vulnerable members of the population by providing social assistance to internally displaced persons, low-income families, and others.

Even before the full-scale war, the SESU had been actively demining its territory because shells from the First and Second World Wars could still be found all over the country. Roman has been doing this since 2006 in his native Luhansk region. Roman and his crew even worked side by side with archaeologists and excavated catacombs, burials, old German dugouts, helmets, and firearms while searching for the old mines and munitions. The archaeological findings were collected for the museum in Rubizhne. Now that museum is in ruins – it was destroyed by Russia’s army.

After Russia started its hybrid war with Ukraine in the Donbas area in 2014, Roman and his crew also had to work with modern Russian explosives. However, as he explains, in 2022, he observed some new kinds of ammunition, and the intensity of work increased exponentially. Along with that, new challenges emerged. From psychologically more difficult operations to more dangerous ammunition and constant attacks from Russia, the work of a deminer today is radically different from peacetime archaeological excavations.

Face to face with the traces of the Russian occupation

With the beginning of the full-scale invasion of Russia in 2022, Roman's squad, along with all the equipment, was evacuated from Rubizhne. Until May 12, 2022, the city was an arena for heavy fighting, after which the Kremlin army occupied what was left of it: bombed-out houses, burned buildings, and empty, broken streets.

"It's very difficult to leave your home, where you've lived for 20 years, knowing you will never see it again. All I had with me was my uniform. Everything else stayed there, in my apartment," Roman sighs.

He and his crew traveled more than 1,000 kilometers from Rubizhne and temporarily moved to the city of Rivne in western Ukraine. But this wasn’t their final stop: as soon as the Ukrainian army pushed out Russia’s troops from the Kyiv region, Roman and his team, together with other most experienced demining groups, were assigned to demine the liberated area of the Kyiv region.

Usually, each demining group has its own task and area to work in: some demine the fields, some demine the roads, some demine villages, and some cover demining requests from local residents who find unexploded ordnance. When the Kyiv region was liberated, Roman and his crew were assigned to Bucha. Before the full-scale invasion, it was a cozy town with over 30,000 residents. But the world came to know a different Bucha—with remnants of fighting vehicles and bodies of civilians scattered on the streets. The mass killing of Ukrainians during the Russian occupation of the city in March 2022 became one of the darkest pages of Russia's war against Ukraine. According to the latest data from the National Police of Ukraine, as of March 2024, 422 bodies of civilians were found in Bucha, and the number spikes to 1,190 bodies if an area near the city is also considered. However, these figures are still not final.

Roman and other deminers were among the first to enter the city after its liberation. He believed he was prepared for the possible scenes he might encounter there: with the start of the hybrid war in 2014, Roman was captured and, therefore, knew about the kinds of torture, psychological pressure, and death threats that the people of Bucha may have faced under occupation. However, the reality turned out to be even harsher.

"When we arrived in the Kyiv region, I saw the bodies of civilians lying at gas stations. I saw children burned in cars. When we were driving there, we thought we knew what to expect and were mentally prepared, but still, the reality was too overwhelming—it was impossible to be ready for this. I will never forget it," recalls Roman.

Although the demining team's primary task was to clear the town of unexploded ordnance, they also ended up helping exhume the bodies of civilians from mass graves because there was a risk of them being mined. The deminers of the State Emergency Service needed to check every meter of the city before civilians were allowed to return.

"We had to demine cots and civilian kitchens in apartments. We also demined the bodies of the dead," says Roman. His team went door to door to make sure every building and every apartment in the city was safe. While doing so, they also witnessed traces of how Russian soldiers lived there during the occupation.

"I recall the house of an elderly couple in Bucha. Russia’s soldiers killed them, covered them with some blankets, and lived there near their dead bodies, drunk," recollects Roman with disgust.

Removing the "petals" of war

According to Roman, if coping with the horrors in the Kyiv region was psychologically difficult, then working in the Kharkiv region, where Roman's team was transferred shortly after the region’s liberation in the fall of 2022, was exhausting and challenging workwise. The area of their responsibility was the city of Balakliia, which endured Russian occupation for seven months. Roman recalls his first impression after entering the city: empty streets with almost no people.

The Kharkiv region is extremely polluted with mines. According to the Balakliia City Council, more than 28,000 explosive devices were discovered in the Balakliia area in the first five months after the de-occupation.

However, unlike Bucha, where Roman's brigade had to demine residential buildings, in the Kharkiv region, they mainly worked in the forests on the outskirts of Balakliia, looking for booby traps and PFM-1 mines (scatterable high explosive anti-personnel land mines). PFM-1, also known as "petals," is a tiny, hard-to-see type of mine that can be easily scattered in large numbers from mortars or aircraft. "Many people in Balakliia were hurt after the detonation of the "petals." There are dense forests around the city, and they are full of them," explains Roman.

Bombs and mines left by Russia’s forces are generally much more dangerous than the World War II explosives. "The old ammunition had fewer chances to explode, and there were no "surprises" as we have now," Shutylo explains.

Such "surprises" can be tripwires, complex traps for deminers, etc. Roman saw them in heavily mined Bucha, in the areas of the Kharkiv region that the crew had to check, and in Kherson, where he and his team were transferred in November 2022.

In the Kherson region, Roman's team dealt with all kinds of explosives, but they mostly worked with cluster munition (submunitions). According to him, these behave unpredictably and can explode even if a person approaches them or because of a temperature change.

"What are submunitions? Imagine a big rocket that contains 680 of such small submunitions in cartridges. The big rocket flies, and these cartridges are scattered. Each cartridge resembles a 0.33-liter jar. Many people died because of them," says Shutylo.

Under shelling in the rain and heat

Roman and his team spent more than a year clearing the liberated territories of the Kherson region of mines and explosives. At first, they worked in the city of Kherson, checking buildings in the city and nearby villages to ensure they were safe for use. But within a month, they were transferred to the village of Posad-Pokrovske on the border of the Kherson and Mykolaiv regions.

Over 2,000 people lived here before the full-scale invasion. Although the village was not occupied, the locals had their own terrible experience of the war because the front line was on its outskirts. Posad-Pokrovske was badly affected by endless shelling. Most of the houses here were destroyed. Almost all residents left. Those who remained were forced to live in temporary modular houses.

To ensure the locals' safety, Roman and his team worked every day, starting at 8 a.m. Sometimes, they worked in pre-planned areas, and sometimes, they processed requests from local residents who found suspicious objects in their yards.

"We worked under all weather conditions because it was necessary to restore electricity and gas to people. We worked alongside electricians, utility workers, and various services," Roman recalls.

It was difficult in the rainy season, but in the warm, dry season, as it turned out, the work was no easier. "It became even more difficult when the grass grew again—as it reaches the knees or the waist, the search for ammunition becomes more complicated, and the risks for deminers increase," explains Roman.

To top it all off, SESU deminers, such as Roman and his crew, are often fired upon by Russia’s forces. He is convinced that the Russian army is deliberately targeting demining specialists. "They are watching us, blocking our roads. Once, they blew up a car with my crew. They are watching and waiting for us," he explains. Some of his colleagues have died. For example, on May 6, 2023, Russia’s military fired at a group of deminers in the Kherson region. Six of the deminers were killed, and two more were injured. "Later, my team went to look for them. To collect the bodies," the deminer recalls.

Despite all the risks, Roman and his team continue to search for and neutralize unexploded ordnance every day. They completed their task in Posad-Pokrovske and returned to demining operations in the Kharkiv region.

"The war has changed my workmates: they have become more responsible, more loving. We’ve become not just a team but one family. I also have colleagues who were killed or wounded, but it's hard to talk about it," says Roman. However, he is ready to do the job as long as he can: "Ukrainian military forces do what is much more difficult than what we do, but the guys stand their ground. So, there is no way back for us. We have to move forward.

All photos provided by the SESU.

Comments (0)